by Collin Eaton

Erives Enterprises, a trucking company in this Texas border city, recently capped its best year ever, hiring workers and handing out raises as its business hauling everything from cars to snowmobiles boomed alongside the factories making the products across the Rio Grande.

Despite the international border, El Paso and its Mexican neighbor, Ciudad Juarez, have knitted themselves into a single, interdependent economy, especially since 1994, when the North American Free Trade Agreement lowered barriers to trade between the United States, Mexico and Canada.

As trucks owned by Erives and other local companies carry billions of dollars in merchandise in long, lumbering lines across the border, at least one in every four jobs in El Paso can be traced to manufacturing plants in Juarez.

But the fate of this link between Mexican factories and Texas companies hinges on fraught negotiations to update NAFTA, scheduled to resume in Mexico City later this month. Businesses on both sides of the border are increasingly worried that President Donald Trump will follow through on his threat to pull the United States out of the treaty, undermining the free flow of goods and services that has sustained them for more than two decades.

“If NAFTA ends, we’re going belly up,” said Angel Ponce, who oversees sales at Erives. “The business will literally go away.”

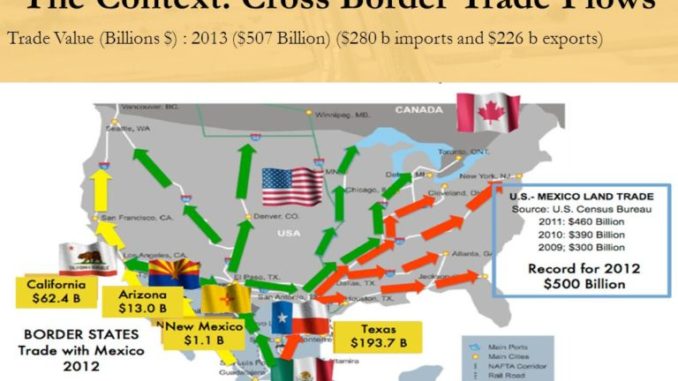

Erives, which employs more than 200 people, is just one of the thousands of companies across Texas that have prospered from trade with Mexico and fear disaster should NAFTA unravel. Few states have as much at stake as Texas in the NAFTA negotiations.

Mexico is the destination for 40 percent of the state’s exports — some $90 billion in goods alone were sold to Mexico in 2016 — and an increasingly important market for the Texas and Houston energy industry, which exports natural gas and fuels to the growing market south of the border.

In El Paso, businesses from warehouses to accountants to financial services depend on the maquiladora industry in Juarez. The end of NAFTA, analysts said, would likely push Mexico into recession and disrupt supply chains, leading to layoffs and bankruptcies in El Paso and slower economic growth across Texas and the United States.

“Everything could decelerate,” said Thomas Fullerton, a professor of economics at the University of Texas at El Paso. “Unnecessarily.”

Already, the uncertain future of NAFTA and the protectionist outlook of the Trump administration has hurt investment on the Mexican side of the border and threatens economic growth in El Paso, business and development officials said. A 2011 study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas found that each 10 percent increase in manufacturing output in Juarez boosted transportation employment in El Paso by more than 5 percent.

“People forget these economies are truly integrated,” said Cindy Ramos Davidson, chief executive of the El Paso Hispanic Chamber of Commerce. “If NAFTA isn’t renegotiated, you’ve broken a relationship.”

Viewed from an airplane or the mountains that surround El Paso and Juarez, rows of low-level buildings dot each side of the border: automotive, electrical products and aerospace manufacturing plants on the Mexican side, warehouses to store goods on the other.

Both cities have prospered. In 2017, Juarez manufacturers increased employment by nearly 5 percent or 13,000 workers, many of whom spend part of their paychecks in El Paso. Mexicans crossing the border on foot – about 18,000 a day – spend about $2 billion a year in El Paso, supporting some 40,000 jobs, according to the Texas Comptroller.

Two industries tied to manufacturing in Juarez — business services and advanced logistics — account for about one in every three jobs in the El Paso metropolitan area, according to Workforce Solutions Borderplex. Unemployment in the El Paso area, which stood above 12 percent when NAFTA went into effect in January 1994, fell to record low of 3.8 percent in October.

“These industries will have huge growth over the next 10 years in El Paso,” said Leila Melendez, chief operating officer at the workforce development agency. “We’re really trying to focus on developing that pipeline.”

At Erives Enterprises, however, executives worry the gains from cross-border trade could diminish quickly. The company’s revenues jumped by about one-third last year, but Ponce, the sales manager, recently received idea of how fragile that business is when the Trump administration announced steep tariffs on imported washing machines.

The appliance maker Electrolux is Erives’ largest customer, shipping 200 truckloads of appliances, including washers, each month. If Electrolux were required to pay those tariffs, it would mean at least a 15 percent drop in monthly shipments, Ponce estimated. Fortunately for Erives, Electrolux products are exempt from the U.S. tariff, an Electrolux spokeswoman said.

While Erives dodged that bullet, Ponce said, the end of NAFTA would add tariffs to a long list of products, raise prices and hurt consumer demand. That would mean fewer truckloads and fewer jobs.

“We’ve been intrinsically intertwined for hundreds of years with Mexico,” said El Paso Mayor Dee Margo. “We’d have an economic downturn, probably, if you’re increasing fees. Certainly you’d be looking at less capital investment and an impact on employment.”

Trump’s rhetoric disparaging NAFTA and Mexico itself has already hurt investment. In December 2016, shortly after the U.S. election, Santiago Medina, then a project manager at one of the world’s largest contract manufacturers, took a call from his bosses — one that likely cost jobs in Juarez and El Paso. The project he was overseeing, a $400 million factory planned for Juarez, had been canceled by his company’s U.S. client, which he declined to name.

“Everything was ready; we were ready to hire people,” said Medina, now a business development director at medical device maker Seisa in Juarez. “The contractor shut down the project because the customer was scared about the implication of investing in Mexico” after Trump’s election.

Such stories have added to local concerns about the future of NAFTA. K. Allen Russell, chief executive of El Paso manufacturing company Tecma, said he has heard of several large projects getting delayed or scrapped over the past year because of the uncertainty of U.S. trade policy. “We hear that everyday,” he said.

U.S. Rep. Henry Cuellar, D-Laredo, said many companies and trade groups initially thought Trump’s anti-NAFTA rhetoric was just political posturing. But now they are beginning to doubt a deal will get done as negotiations have dragged into 2018. “Behind the scenes, they’re starting to get a little worried,” Cuellar said.

Since the early days of his campaign, Trump has railed against NAFTA, calling it “one of the worst things to ever happen to the (U.S.) manufacturing industry.” That became a rallying cry for Trump in states like Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Indiana, where the loss of manufacturing jobs over four decades has hit the hardest.

“You go to New England, you go to Ohio, Pennsylvania, anywhere you want,” Trump said in a debate with former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, “and you will see devastation, where manufacturing is down 30, 40, sometimes 50 percent.”

Indeed, the first few years after the trade agreement took effect were rocky ones for El Paso. The border city, once famous for its boots and jeans makers, lost more than 25,000 manufacturing jobs.

But economists say it’s difficult to weigh the costs of NAFTA against its benefits. The costs are often obvious, tallied by a count of shuttered plants and lost jobs. But benefits are harder to quantify as they spread among millions of consumers who can afford a better standard of living because of lower prices for household goods, said Roberto Coronado, vice president in charge at the Dallas Fed’s El Paso branch.

One thing that is quantifiable, however, is how trade with Mexico benefits partners in the United States. For every $1 in products that the United States imports from Mexico, 40 cents of the content come from components made in the United States. Compare that with the 4 cents of U.S. content that comes with each dollar the nation imports from China, Coronado said.

“Seventy-five percent of the stuff we bring from Mexico is intermediate goods,” he said, “and that means it’s stuff that goes back and forth.”

For example, when El Paso manufacturer MFI International makes a mattress, it buys materials like zippers and threads in the United States, and gathers them for the first round of design, cutting and stitching in El Paso. Then it sends the mattress to its plant in Juarez for further assembly, trucks it back to El Paso and ships it somewhere in the United States.

Manuel Gomez builds shipping containers at American Packging and Supply, Inc., on Thursday, Feb. 1, 2018, in El Paso, Texas. ( Brett Coomer / Houston Chronicle )

MFI employs 600 workers, split between plants in El Paso and Juarez.

“The jobs I provide at my plant in the United States,” said Cecilia Levine, chief executive of MFI, “are related to the ones I provide in Mexico.”

In 2015, the most recent data available, trucks carrying manufactured goods crossed the border at El Paso 760,000 times, contributing to economic activity that supported roughly 130,000 jobs in Texas, according to the Texas Comptroller. El Paso, the second-largest port of entry between the United States and Mexico, exported $24.6 billion in goods last year.

Trade was the economic engine that pulled Nicole Grado’s El Paso packaging company out of a financial tailspin when U.S. economy slowed after the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks.

American Packaging, the business Grado started with her father 17 years ago, was strapped for cash. For a time, Grado didn’t think her company would be able to repay its $100,000 Small Business Administration loan.

But after a six-month rough patch, orders for packaging started rolling in as Mexican manufacturers revved up. Alongside the maquiladoras, American Packaging has grown almost every year since, distributing custom and commodity packaging from El Paso and employing nine workers.

The company occupies a building that once housed seamstresses sewing and cutting garments, replacing at least some of jobs that moved offshore with the apparel industry.

Those jobs, though, didn’t shift to Mexico; they went to China.