Does high-school recruiting help more students graduate?

Over the past decade, Hispanic students have graduated high school and entered college in growing numbers. Yet the rate of Hispanic college completion has remained persistently lower than that of whites and other ethnic groups in the United States: only 23 percent of Hispanic adults hold any postsecondary degree compared to 42 percent of all adults. Helping raise the Hispanic college graduation rate is an urgent goal, given the persistently high rate of poverty among Hispanic families, growth of the Hispanic population to account for one in five college-age Americans, and mounting concerns about racial and economic inequality.

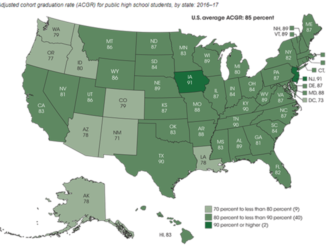

One potential strategy involves helping high school students broaden the set of colleges to which they apply and enroll. Hispanic students may be more constrained in their college-selection process than other groups, and are far more likely to attend two-year colleges, which typically have far lower graduation rates than four-year institutions. Just 56 percent of Hispanic college students enroll at four-year institutions compared to 72 percent of non-Hispanic white students. Hispanics are also less likely than members of other ethnic groups to earn a bachelor’s degree: 15 percent of Hispanics have a bachelor’s degree, compared to 33 percent of whites, 54 percent of Asians, and 22 percent of African Americans (see Figure 1).

We examine an intervention designed to expand Hispanic students’ college exposure: the National Hispanic Recognition Program (NHRP), a College Board initiative that identifies top-performing Hispanic students based on their 11th-grade Preliminary SAT/National Merit Scholarship Qualifying Test (PSAT/NMSQT) scores. NHRP changes two key features of their high-school experience. First, the College Board notifies students and school staff, such as school counselors, about this prestigious award. Second, with the student’s permission, the College Board shares lists of NHRP honorees with postsecondary institutions looking to recruit Hispanic students. We measure the impact of this early, pre-application recognition on students’ enrollment decisions, as well as their college persistence and degree attainment rates.

We find evidence that the program induces students to apply to and attend more elite institutions, shifting students from two-year to four-year institutions as well as to out-of-state and public flagship colleges, all areas where Hispanic attendance has lagged. Overall, NHRP recipients are 1.5 percentage points more likely to enroll at a four-year institution, 5 percentage points more likely to attend both an out-of-state college and a recruiting institution, and 3 percentage points more likely to attend a public flagship institution. The program’s impact on college completion is generally positive but statistically insignificant; however, we find sizable increases in bachelor’s degree completion among students who otherwise were at the highest risk for dropping out of college.

Together, these findings demonstrate that college outreach can have substantial impacts on the enrollment choices of Hispanic students and can serve as a lever for institutions looking to draw underrepresented, academically talented students.

An Elite Honor for Hispanic High-School Students

NHRP was founded in 1983 by the College Board, a nonprofit that advocates for expanded access to higher education and administers college-level exams such as the SAT. Similar in spirit to the National Merit Scholarship Program, an annual academic scholarship competition conducted by the National Merit Scholarship Corporation, the NHRP was designed to recognize outstanding Hispanic high-school students and encourage them to enroll in college. The program identifies the top 2.5 percent of Hispanic students each year based on their performance on the 11th-grade PSAT/NMSQT, which assesses skills in math, critical reading, and writing. About 5,000 students are recognized by the NHRP annually, with California and Texas having the largest numbers of NHRP scholars.

To establish eligibility requirements, the College Board analyzes PSAT/NMSQT performance among Hispanic students within six different geographic regions each year, and then identifies the score that separates the top 2.5 percent of test-takers from other students in that region. The eligibility cutoffs range from the low 180s to the mid-190s out of a maximum of 240 points. Students with qualifying scores are invited to join the program. To be formally accepted, they must then verify that they are at least one-quarter Hispanic, and their high school must document that the student’s junior year cumulative GPA is at least 3.5. Almost all students who are initially deemed eligible for the program are able to satisfy both requirements.

Students recognized by NHRP are more likely to live in cities and attend large high schools with significantly more low-income and Hispanic students, compared to white students with similarly strong PSAT/NMSQT scores. They are also about four times as likely to have families with incomes below $50,000 and to have parents who did not graduate from high school. Compared to their white peers, they take and pass fewer Advanced Placement (AP) exams, and are less likely to attend four-year or out-of-state colleges.

The program does not provide any direct financial reward to students but has the potential to influence their college preparation and application decisions in other ways. The College Board sends a letter directly to students that congratulates them for being in the top 2.5 percent of Hispanic students nationwide—a clear and perhaps surprising recognition of academic ability. Students are encouraged to participate in the program and list it on college, scholarship, internship, and job applications. The organization also informs school counselors of newly recognized students, and asks that the staff members help the students complete the necessary paperwork and apply to top universities as well as honor them through some type of school recognition.

In addition, with the student’s permission, the College Board shares a list of NHRP recipients with about 200 four-year postsecondary institutions hoping to recruit academically exceptional Hispanic students. These recruiting institutions, as measured by rankings, graduation rates, and average SAT scores published by Barron’s Profiles of American Colleges, are more competitive, on average, than other, non-recruiting four-year institutions attended by Hispanic students who fall just short of qualifying for the NHRP program. They are also slightly larger and more expensive, though the percentages of enrolled students identifying as Hispanic are comparable at recruiting and non-recruiting schools.

Thus, NHRP status can affect students’ college-going decisions and degree completion through two primary mechanisms. First, research has shown that many high-performing students do not apply to elite institutions even though they are eligible, and that informing them about college options can shift where students apply and ultimately enroll. Second, recognized students often receive targeted outreach and financial incentives from colleges that actively recruit NHRP scholars as part of their efforts to increase diversity among their students.

Data and Method

To conduct our analysis, we constructed a national sample of all Hispanic 11th-grade PSAT/NMSQT takers in the U.S. from the graduating high-school classes of 2004 to 2010. We then linked individual-level records to a number of auxiliary data sources from the College Board and the National Student Clearinghouse, including basic demographic information, the high school they attended, eventual college enrollment, their history of SAT attempts, the institutions to which they sent their SAT scores, and AP participation. We also included information from the Common Core of Data (CCD) and the Private School Universe Survey (PSS), which include data about the size, demographics, and geographic location of the high school attended when each student took the PSAT/NMSQT, as well as the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), which includes the characteristics of postsecondary institutions.

We study the impact of NHRP on student outcomes using what is known as a regression discontinuity design. This approach takes advantage of the program’s initial eligibility requirement: a numeric cutoff. Because students are unable to precisely manipulate their PSAT/NMSQT scores, those scoring just below the cutoff should be essentially identical to those whose scores are just above. Furthermore, because the eligibility cutoffs vary by year and are unknown in advance, and because students have only one opportunity to take the PSAT/NMSQT in 11th grade, there is no way for students to “game” the system. We restrict our analysis to students whose PSAT/NMSQT scores are within 15 points on either side of the cutoff, to produce a data set of approximately 58,000 students across all years.

Our preferred results adjust for the region and year in which each student took the PSAT/NMSQT, as the eligibility cutoff varies by region and year. This adjustment also accounts for unmeasured differences in high school and college policies, such as state spending on higher education, changes in high school curricula, and the relative competitiveness of college admissions in a given year. We also confirm that we obtain similar results when we control for student characteristics measured at or before the PSAT/NMSQT, including sex, parental education, family income level, whether a student took the PSAT/NMSQT in 10th grade and his or her previous score, indicators for ethnic background (for example, Mexican, Cuban), and controls for the type of high school attended, including affiliation (public or private), urbanicity (that is, city, suburban, rural), size, and concentration of Hispanic students.

NHRP eligibility has a significant effect on college attendance patterns. Eligible students are 5 percentage points—almost 16 percent—more likely to attend colleges that recruit Hispanic students through NHRP (see Figure 2). They are also more likely to attend out-of-state and public flagship institutions by roughly 5 and 3 percentage points, respectively, with much of that effect due to students opting to attend recruiting institutions. In addition, students are approximately 1.5 percentage points more likely to enroll at a four-year institution, with about two-thirds of this effect driven by movement away from the two-year sector (see Figure 3).

Closer inspection reveals a group of seven universities that account for virtually all of the shift toward NHRP-recruiting schools, with eligible students 5.8 percentage points more likely to attend one of these schools than their non-NHRP peers. Given a baseline of 4.1 percentage points, this means students were more than twice as likely to attend one of these seven core recruiting institutions as a result of the program.

For privacy reasons, we cannot identify the particular colleges, all of which are large public institutions located outside of California and Texas. Three are included on Barron’s “Highly Competitive” list, four serve as state flagships, and all seven offer substantial financial aid for NHRP scholars and make this information easily available to prospective students on their websites.

Given the sizable shift of students toward recruiting institutions, the primary mechanism by which NHRP affects students’ initial college choices appears to be a combination of direct college outreach and financial aid. An alternate, or perhaps complementary, theory is that NHRP induces students to improve their academic preparation in high school, making them more attractive candidates to these colleges. We investigate this possibility, however, and find no evidence that NHRP scholars improve their academic performance during their senior year; they do not take or pass more AP exams, score higher on the SAT, or retake the SAT more often than non-NHRP students.

We also examine whether NHRP-eligible students are more likely to earn a bachelor’s degree within four years. Our overall results are positive though statistically imprecise, with NHRP eligibility increasing degree completion by 1.3 percentage points. We also examine the effects of the program on six-year graduation rates. The results are noisier due to a smaller sample size, but follow a similar positive pattern. These positive but imprecisely estimated completion impacts suggest that, at the very least, high-performing Hispanic students are not harmed by enrolling at colleges that they may not have ordinarily considered.

The fairly small effect on overall completion conceals much larger effects on where NHRP-eligible students earn their degrees. The percentage of students earning bachelor’s degrees in four years at recruiting institutions increases by 4 percentage points. Moreover, NHRP eligibility increases the share of students who earn degrees outside their home state by 2.8 percentage points, or 16 percent, suggesting that NHRP helps to disperse high-achieving Hispanic students by geographic region. We estimate that nearly 60 percent of students induced to attend out-of-state colleges ultimately earned bachelor’s degrees in four years. When the time frame is extended to six years, this jumps to nearly 80 percent. This evidence casts doubt on the prevailing sentiment that high-performing Hispanic students may struggle to flourish in unfamiliar or uncomfortable postsecondary environments, or when separated from immediate family structures.

Who Benefits the Most?

Given the variation in high school environments, college quality, state policies, and proximity of recruiting colleges across the United States, we should expect a range of responses to NHRP eligibility depending on where students reside. When it comes to college enrollment, we do find strong regional differences, with students in the western and southwestern regions driving the overall results. There is almost no impact on attendance patterns for students in the other four regions, except for an increase of 2.4 percentage points in the likelihood of attending one of the seven core recruiting institutions. That figure, over a baseline of 0.2 percent, indicates the strong effects of college recruitment even in the presence of distance. Perhaps surprisingly, given the cross-regional differences in enrollment patterns, the effects of NHRP on degree attainment are relatively equal across regions, measuring 1.1, 1.4, and 1.6 percentage points in the West, Southwest, and other regions, respectively.

Are there other student characteristics that coincide with varied effects of the program? We found the outcomes are driven entirely by students at public high schools. The strongest effects are among students whose high schools have the highest concentrations of Hispanic students or are in more rural environments (see Figure 4). These students experience the largest increases in four-year college enrollment and out-of-state college enrollment, as well as an increase of 2 to 6 percentage points in the likelihood of attending a college in the “Most Competitive” category. We also find sizable increases in four-year degree completion, ranging from 4 to 8 percentage points among the types of disadvantaged students who typically have the lowest completion rates.

We also examine differences in program impacts based on student academic performance, as measured by a student’s SAT score. We find the largest impact for students whose SAT scores are in the bottom third of NHRP-eligible students—those traditionally at the highest risk for dropping out of college. These students’ four-year bachelor’s degree completion rates increase by more than 4 percentage points, or 10 percent. In addition, their college attendance increases by 10 percentage points at recruiting colleges, and by 4 percentage points at both four-year institutions and “Most Competitive” colleges. By contrast, the impacts for students whose SAT scores were in the highest third of all NHRP-eligible students were either considerably smaller in magnitude or indistinguishable from zero.

Implications

The National Hispanic Recognition Program has a meaningful impact on the college-going decisions of high-achieving Hispanic students. However, simply offering recognition for academic performance is insufficient for achieving the college enrollment and completion effects documented in this study. Rather, our results suggest that college enrollment and completion can be positively influenced by higher-touch efforts on the part of colleges, such as the targeted recruitment and financial aid offers that accompany NHRP recognition.

Such active outreach and financial support are particularly important for students and high schools with fewer resources, and stepping up efforts to publicize these opportunities among high-achieving underrepresented students may be an effective way of increasing their postsecondary success. Our results also confirm that colleges actively seeking to enroll high-performing Hispanics can accomplish those goals, which is consistent with a mission of creating a diverse and academically strong student body.

Taken together, our results reveal several straightforward lessons. First, inducing students to attend out-of-state colleges likely requires large financial incentives, given that all the observed out-of-state shifting in this study is driven by colleges known to provide large student aid packages. Second, this program allows colleges to effectively recruit Hispanic students attending a wide variety of high schools. The consistency of effects suggests that NHRP serves as an effective recruitment tool for Hispanic students from diverse backgrounds. Third, student responses are regionally specific, emphasizing the role of the higher-education marketplace and local options in selecting which colleges to attend.

Perhaps most important, the results of this program show that high-achieving Hispanic students succeed at selective post-secondary institutions, and that any culture shocks from unfamiliar environments are not impeding completion. We find the opposite, as NHRP scholars from predominantly Hispanic high schools actually experience large increases in four-year bachelor’s degree completion rates. These findings challenge the narrative that unique cultural circumstances and intense family and community ties shared by Hispanic students might impede their success at colleges far from home.

Oded Gurantz is an Institute of Education Sciences fellow in the Stanford University Graduate School of Education. Michael Hurwitz is senior director at the College Board. Jonathan Smith is an assistant professor of economics at Georgia State University. A more detailed account of this investigation can be found in the Winter 2017 issue of the Journal of Policy Analysis and Management.