by Alex Nowrasteh

There are many aggravating tropes that keep reemerging in the debate over immigration policy but one of the worst is that every problem with the U.S. immigration system is the result of the supposedly perfidious Mexico. Changes in Mexican law and policy certainly have an impact on immigration to the United States but it is not true that our laws would operate wonderfully even if foreign governments had policies to support them. Those who blame Mexico should, at the minimum, get their stories straight.

In many versions of this tale, the Mexican government is hypocritical because its immigration laws are strict yet it complains about laws like SB 1070 in Arizona and the deportation of Mexican citizens from the United States. Talk radio show host Rush Limbaugh famously used this rhetorical tactic when sarcastically (maybe?) proposing a series of immigration reforms that mirrored the worst of Mexican immigration law in 2007.

The Mexican government fiercely criticized the passage of Arizona’s SB 1070 in 2010, a bill that forced state and local police to enforce federal immigration laws. When then-President of Mexico Felipe Calderon visited the White House and intended to complain about the law directly to President Obama, Representative Ted Poe (R-TX) said, “I wonder if they’ll discuss whether or not Calderon supports his own country’s immigration policy.” Both Limbaugh and Poe rightly criticized Mexico’s famously restrictive, self-destructive, and hypocritical immigration policy.

Partly in response to the American criticism, Mexico gradually reformed its immigration laws beginning in 2008. In that year, Mexico reduced the punishment for illegal entry to a maximum fine of 5,000 pesos, down from a potential ten-year prison sentence. They also created a temporary agricultural guest worker visa program for agricultural laborers from Guatemala and Belize working in Mexico’s southern states. In 2010, the Mexican government stated that illegal immigrants would not have to fear immigration enforcement when reporting human rights violations or receiving medical treatment.

The Mexican government did not stop there. The Mexican Congress passed a Migratory Act in 2011 that went into effect on November 1, 2012. This law replaced the Mexican General Law of Population that was the source of their restrictive immigration laws. Among other things, the new Mexican immigration law allowed immigrants and migrants equal access to Mexican courts, reduced the power of local police to enforce immigration law, reformed the humanitarian admissions system, simplified entrance and reduced residency requirement by, in part, creating a points system, and created a three-day regional visitor’s visa for people from neighboring countries. In other words, Mexico liberalized and expanded its legal immigration system. Although Mexican reforms did not go far enough, they were a significant step away from protectionism toward a more liberal immigration regime.

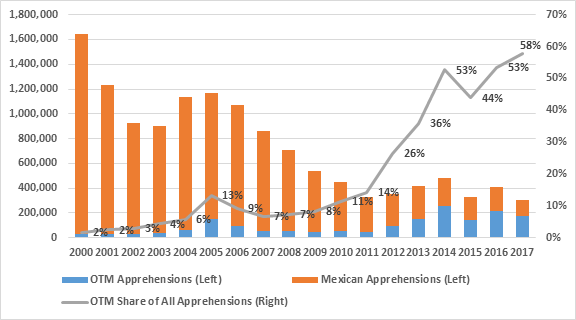

Shortly after the Migratory Act of 2011 went into effect, the number of Unaccompanied Alien Children (UAC) apprehended by Border Patrol skyrocketed (Figure 1). The change in Mexican immigration law allowed Central Americans to travel to the U.S. border in greater numbers which, combined with the worsening economic and crime problems in Central America, helped exacerbate a surge of non-Mexican (OTM) illegal immigrants and asylum seekers who were overwhelmingly from south of Mexico’s border (Figure 2). Other non-Mexican legal changes like the Central America-4 Border Control Agreement, that created a visa-less Central America among El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua, also made it cheaper for migrants or UAC from those countries to make it to Mexico and then to the United States.

Figure 1

Southwest Border Monthly Border Patrol Apprehensions of Unaccompanied Alien Children

Source: Customs and Border Protection.

Figure 2

Other than Mexican and Mexican Southwest Border Apprehensions

Source: Customs and Border Protection.

As the surge of UACs heated up over the summer of 2014, the American government started pushing Mexico to strictly enforce its own immigration laws before the migrants got the American border. All of a sudden, Mexico’s immigration laws had become too lax and American politicians and commentators were furious. The hyperbole from the U.S. government rose to such levels that Marine Corps General John Kelly, then-SOUTHCOM chief, said, “[m]any argue these threats are not existential and do not challenge our national security. I disagree.” The Soviet Union would have been an existential threat if it attacked the United States during the Cold War but it strained General Kelly’s credibility to claim that a surge of UAC and other migrants, equal to a small percentage of legal admissions that year, was a threat to the country’s existence.

During the 2016 presidential campaign, then-candidate Donald Trump blamed the Mexican government for America’s illegal immigrant population and frequently said that he will build a wall that Mexico will pay for. The Mexican hypocrisy of defending illegal immigrants in the United States while having a strict immigration policy on its own southern border rankled Trump and many of his supporters despite recent changes to Mexican immigration law.

Recently, President Trump criticizedthe Mexican government for not enforcing its immigration laws well enough in order to stop the caravan of about 1,000 Central Americans traveling to the U.S. border to ask for asylum. As soon as the Mexican government largely broke up the caravan, President Trump quickly reversed course and praised Mexican laws for being stronger than American laws.

Mexico has serious problems. Although it has made some strides in recent years, low economic and individual freedom have produced endemic corruption. The U.S.-subsidized war on drugs has created a level of violence that occasionally reaches civil-war-level death tolls. Regardless of those problems, Mexico should cease to be the blame for the failures of American immigration policy. It is easy for American politicians to blame foreign governments rather than take responsibility for a sclerotic American immigration system that Congress has failed to substantially reform in almost three decades. Recognition that Mexico has serious problems is at odds with the standard political received-wisdom that we should outsource much of our immigration enforcement policy to the very same government with so many problems. Better American laws that allow more legal immigration through a cheaper, simpler, and better-enforced system will do a lot more to bring order to the border than relying on the Mexican government. The policies of foreign government affect immigrant flows to the United States and no reasonable person could claim otherwise but the American political tradition of criticizing Mexican immigration law for either being too strict or not strict enough based on the U.S. news cycle should stop.

Alex Nowrasteh is an immigration policy analyst at the Cato Institute’s Center for Global Liberty and Prosperity.