by Anne Hyslop

As Senator Lamar Alexander explained it, the driving force behind the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) was that “everybody from the teachers’ unions to the governors to the school boards were irate at being told so many things to do from Washington about how to educate children.”

If that’s true, boy did ESSA deliver. Two years later, the issue is no longer faraway D.C. bureaucrats telling states what to do. The issue is states aren’t telling Washington what they’re doing.

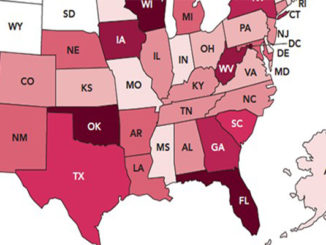

That’s the takeaway from the second round of independent reviews of state ESSA plans released by Bellwether Education Partners and the Collaborative for Student Success. As an external consultant working with the Bellwether team, our reviews focused on some of the most critical areas of ESSA: how states plan to set up accountability systems that provide clear information about schools, based on multiple measures, to parents and the public and how they identify and support the lowest-performing schools and schools with struggling subgroups.

These provisions lie at the heart of ESSA’s promise to help every student succeed. Yet across all states – the 17 that submitted plans in April and the 34 in September – the reviews “found state ESSA plans to be mostly uncreative, unambitious, unclear, or unfinished.”

Reasonable people can disagree over what’s “ambitious,” but it’s hard to deny there’s a problem if states don’t provide basic information about how they’re meeting core requirements in the law. Here are a few examples:

- In Florida, one in 10 students are English learners, yet the state doesn’t identify a single non-English language spoken to a significant extent and omits English learners’ language proficiency from its A-F school grading system. Here’s another head-scratcher: Florida defines a “consistently underperforming subgroup” in a way that isn’t even based on subgroup results.

- New Hampshire conveniently left out that a new state law prohibits it from requiring annual testing in third through eighth grades – a key tenet of ESSA – and doesn’t describe how it will procure a new test in 2018 or convince districts to administer it.

- Virginia will set aside nearly $16.8 million annually for interventions that are supposed to be “evidence-based,” yet the state’s plan for accountability and school improvement doesn’t actually use the word “evidence,” let alone explain how it will support districts in identifying evidence-based strategies.

- Texas’s method for including subgroup results in its A-F school grades is described in three sentences (three!) of its plan. This Closing the Gaps component “ensures students are doing well regardless of racial group, special education status, and socioeconomic status for all indicators required by state law and ESSA.” How, exactly, it ensures that is left off the page.

Missing details in the first set of plans were, perhaps, understandable. The Obama administration’s ESSA regulations and related state plan template had been rescinded only weeks before plans were due – leaving significant confusion about the process. But that shouldn’t have been an issue for states in September who had the benefit of more time and learning from the first group of states. What gives?

Rather than putting their ingenuity, willingness and ability to lead on full display, many states seem to have deliberately submitted as little as possible. On one hand, I can’t blame them. More details could invite more feedback and negotiations with the Department of Education (ED) prior to approval. More details could mean more areas for future federal monitoring or open up the state to additional criticism from political opponents closer to home. More details could also mean more revisions to the plan down the line as policies change.

But on the other hand, it lays bare a troubling reality: The Trump administration simply doesn’t care about compliance with many of the law’s provisions, let alone recognize that states may need help to implement them. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos seems to have adopted a “trust, and don’t bother to verify” attitude. In fact, one state leader admitted that the secretary “stressed local control, and told state chiefs in a closed-door meeting to hand in their plans even if they weren’t totally complete.”

Her words have translated into action – or lack thereof – from the department. On top of repealing the regulations, the revised and hastily drafted new template not only stripped out references to the ill-fated rules but also questions related to key statutory requirements, from stakeholder consultation to how states plan on spending $1 billion in school improvement funds – lowering the bar for approval. Frequently asked questions about ESSA’s accountability provisions are buried under a disclaimer on ED’s website and haven’t been updated – forcing states, districts, advocates and stakeholders to go plan by plan, and letter by letter, to decipher how the law is being interpreted. Questions like how science can be included are being answered by journalists, even though they could easily be addressed in an official FAQ document. That would provide a transparent, verified source of information that everyone benefits from, not just those having private conversations with ED. But despite approving 16 of the 17 plans from April, the Department hasn’t issued a single piece of policy guidance to help explain why changes were needed in submitted plans or to highlight areas of promising practice. In fact, a survey released this week by the Center on Education Policy (CEP) found that a majority of states reported that available federal guidance wasn’t enough or was short on detail. It’s no wonder states delivered bare-bones plans when this is all they had to go on.

The response from some states – submitting the bare minimum to pass muster – inspires little confidence that states are prepared for the responsibilities and flexibilities ESSA gives them, especially when coupled with findings like those in the CEP survey that one-third (or fewer) of states said they had sufficient capacity to carry out ESSA’s school improvement requirements. But even if we give states the benefit of the doubt and assume the details are nailed down somewhere else, the problem remains that the department doesn’t think it’s a problem to expect so little of states.

That’s why outside reviews, like the one from Bellwether and the Collaborative, are so important. They help fill the information gaps the department refuses to address. ESSA ultimately won’t be judged by words on paper but by what happens in classrooms – whether more students are on track to college- and career-readiness, whether achievement gaps are closing and whether low-performing schools are improving. And where they are, we need to understand what states are doing to create those conditions. States may not trust the department enough to give them more detailed information, and ED may have too much blind faith that states will follow the law, but someone – whether it’s journalists, advocacy groups, think tanks or all of the above – needs to both trust and verify what’s happening under ESSA.

Anne Hyslop is a former senior policy advisor at the U.S. Department of Education.