This article is adapted from AQ’s special issue on the U.S.-Mexico relationship.

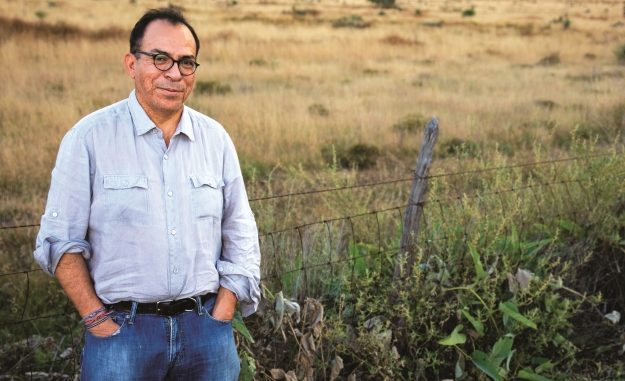

A native of the northern Mexican state of Durango, I spent much of my childhood between El Paso and Ciudad Juárez. As a boy, I stared at a Christmas star shining from the Franklin Mountains in El Paso, wondering whether that was what the First World looked like. Later in life, as a journalist, I have roamed the 2,000-mile border by car and by foot, alone and with colleagues.

These travels have taught me a lot. They’ve made me find the sweet spot of who I am —at home on both sides. And they’ve also given me some perspective on the current debate over walls and tariffs, deportations and so on.

Because, you see, we’ve been here before.

“Those of us (who) have lived along the border have long understood that dealing with Washington’s berrinches is just part of the deal,” Tony Garza, a former U.S. ambassador under President George W. Bush and a native of Brownsville, Texas, told me.

Berrinches means “tantrums,” and their physical manifestations have been around for decades, erected by Democrats and Republicans alike. “I’ve seen physical barriers along the border since I was a kid,” Garza said. “And I’ve seen fences and walls do wonders for the livelihood of coyotes (immigrant smugglers) and politicians, but not much else.”

Some 10 million people live on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border, and residents of the 14 sister border communities largely view themselves as one community. This reality isn’t always appreciated elsewhere, even though the facts are there in plain sight. For example, in a Cronkite News-Univision News-Dallas Morning News poll in 2016, 72 percent of respondents on the U.S. side and 86 percent of those interviewed on the Mexican side said they were opposed to building a wall.

So how do those of us from the border deal with times like these?

Resilience, ingenuity and a good sense of humor help.

Consider Boquillas del Carmen, a tiny Mexican village located across the Rio Grande from Texas’ Big Bend National Park. Here, an innovative crossing connects residents with tourists who hike in the towering Sierra del Carmen Mountains. The crossing was closed after the September 11 attacks, due to fears it was too vulnerable, but reopened in 2013. The “ferry” that takes people back and forth across the Rio Grande is run by Mike Davidson, a Texan outdoorsman and a musician who led the effort to reopen the informal crossing, with the help of other Texans and Mexicans.

Interdependent

For a small fee, tourists and locals visiting relatives hop on rowboats and in a matter seconds they are in Mexico riding burros, eating tacos, and sipping Mexican Coca-Cola in a bottle — or beer, tequila or mescal — with music blaring and the sun blazing. The Americans are then rowed back to the U.S. side, where a border patrol agent and a park ranger keep a close eye on folks as they slip their passports or other documents into a machine that reads the information and verifies they’re legal crossers. Each crosser then picks up a phone and is connected to a Customs and Border Protection officer in El Paso, who can see the person on camera and ask questions if necessary. The process takes just a few minutes.

The semi-automated crossing has breathed new life into Boquillas. The people who live in this area depend on one another. They cannot imagine living with a wall between them.

“People who bought that kind of thing, that you can wall off 2,000 miles, they don’t really have a good grasp of what it’s going to take,” said Davidson. He and others point to the expensive and difficult undertaking of hauling cement and other material and transporting workers to the remote, rugged region.

He worries a wall will change the back and forth way of border life, including his own.

“I’d have to decide which side of the wall I’d want to end up on,” he said.

When he’s not worrying, he’s jamming a mix of Tex-Mex tunes, traditional Mexican music and American rock-and-roll at parties, quinceañeras, baptisms, and weddings on both sides of the border. The group pokes fun at itself, calling themselves Los Pinches Gringos (The Damned Gringos). The band is so affectionately well-known on both sides of the border that few see the irony of the name.

Nothing, however, can heal the wound that writer Carlos Fuentes once eloquently described, a metaphor that acclaimed author Benjamin Alire Saenz said resonates even more today.

“Every border is a wound,” said Saenz, who lives on the border. “Borders are not organic and the lines we mark on the geography of the Earth are offensive. They are scars and wounds we inflict upon the Earth, and ourselves.”

The dividing line

The resilience of residents who have learned to survive — and coexist — despite outsiders’ efforts at division can be seen everywhere you travel in the borderlands. The countryside along Highway 90 between Big Bend National Park and Del Rio in West Texas is so isolated that people on both sides of the border have to depend on one another for survival. In one area, a school was closed and stores abandoned because of dwindling populations. It rained, rained and rained, drops splashing on pavement, making puddles of water on a pink sunset afternoon.

The only constant vehicles were the green and white vans of the border patrol, agents suspiciously peering through windshield-wipers, making sure the border and the rest of the country was safe.

I once walked through an area of the dividing line in Del Rio covered with thickets of carrizo cane, an invasive species that authorities have tried getting rid of by burning it or using a combination of mechanical, chemical and biological methods. And yet the carrizo cane stands firm in swampy land. Much of the land is privately owned and so treacherous that just 115 miles of the 1,200-mile Texas border is fenced today.

Landowners, environmentalists, security experts and Texas politicians have in the past blocked efforts to add more fencing, although Texas Governor Greg Abbott recently identified land between El Paso and Presidio as a possible site for President Trump’s new wall. The rest of the 654 miles of existing border fence is in California, Arizona and New Mexico.

Along stretches of the border, the fence is a patchwork of material, from new wire mesh to sheets of old metal topped with barbed-wire that appear to be slapped together without much thought. This newer bollard-style structure, preferred by the border patrol, is harder to climb, and agents can see through the 18-foot metal posts to view what’s on the other side in Mexico.

For loved ones, the fence provides a rare chance to reach through and touch relatives and wipe away each other’s tears.

On some sections, artists have painted murals on the fence to help residents temporarily forget the imposition that interrupts the otherwise stunning desert landscape, painting scenery over the rust-colored panels in colors that include sky blue.

Talk to people here, and they realize how much economies are interconnected. “I can’t think of anything about a wall that’s ‘beautiful,’” said Marco Haro, 61, who operates a dollar exchange house in Nogales, Texas. “A sad monstrosity. … Our lifeline is across the border, Mexico. Without Mexicans, we don’t exist. Our life is sucked away.”

This view is held in Washington, too, and crosses traditional party lines. Republican Congressman Will Hurd, who represents the largest territory along the border, stretching 800 miles from San Antonio to El Paso, called a wall “the most expensive and least effective way to secure the border.”

“Each section of the border faces unique geographical, cultural and technological challenges that would be best addressed with a flexible, sector-by-sector approach that empowers the agents on the ground with the resources they need,” Hurd added.

His Democratic colleague, Beto O’Rourke of El Paso, agreed. “This wall makes sense if you’re not from here, if you’ve never been here, if you’re scared of Mexico and of Mexicans. It seems like a good emotional response to that fear. But when you live here and you know how interconnected we are and you know friends, or have family on both sides of the border, it seems ridiculous at best and, at worst, it seems like something that is shameful and embarrassing.”

Exaggeration campaign

Other than the hour or so then-candidate Trump spent in Laredo, mostly at a press conference where he stood wearing a white “Make America Great Again” baseball cap, I cannot remember Trump in this border region at any other time. In Laredo, he talked about the personal danger he faced coming to the border, telling an audience of mostly reporters, “I have to do it. I love this country.”

For what it’s worth, the cities on the U.S. side of the border, whether it’s Laredo, El Paso or Nogales, are some of the safest in the United States. But facts didn’t stop Trump from promoting the wall, which represented the cornerstone of his presidential campaign and was central to his immigration policies.

Exaggerated threats have long been a part of life here, too. I’ve walked across the border town of Ojinaga to look for chemical weapons after a U.S. document said terrorists were planning to smuggle the weapons through Big Bend. Even though the information was based on raw intelligence, The Dallas Morning News assigned a colleague and me to spend weeks investigating everything and anything about the claim. Nothing.

I spent an entire day looking for ISIS operatives across the Rio Grande in Anapra, even knocking on doors, following a report in the conservative Judicial Watch that alleged the terrorist group had set up a training camp there.

Again, nothing.

Maybe the only way for people along the border to make their voices heard is by voting in greater numbers. This is already happening in some places. In Nogales, a record number of voters turned out to vote last November. El Pasoans did so too, with a 32-percent increase in turnout, closing the gap between Republicans and Democrats in Texas to nine percentage points, from 19 percent.

“The wall isn’t just a colossal waste of resources,” said El Paso County Judge Veronica Escobar. “It’s also an ugly symbol of xenophobia dreamed up and built by people who don’t care to understand the complexity and importance of the border. Border communities like El Paso and Ciudad Juárez are deeply intertwined because of our families, economy and history, and a wall is an attempt to erode that connectedness.”

From the back patio of my home in El Paso, I recently took in a perfect afternoon and thought of how a wall destroys what so many along the border have tried to build. We are a people who once dared to dream of being not just part of the U.S. and Mexico, but of something bigger: North America, as former President Ronald Reagan called for in 1979.

I could see two countries, three states — Texas, Chihuahua and New Mexico — bound by the Rio Grande, its border lines invisible. A few years ago I marveled at the same sight and wrote words for my book Midnight in Mexico that haunt me today.

I had written then that we’re the same geography — one blood, two countries dancing out of step. Two souls still clashing. Staring into the shadows before me that late afternoon, I realized as well that I was looking at a wound that won’t heal any time soon.

Journalist Angela Kocherga contributed to this report.

Photo Credits: Alliance/DPA/DP; Angela Kocherga; Rick WIlking/Reuters

Alfredo Corchado is a visiting fellow at the Center for U.S.-Mexican Studies program at the University of California San Diego, codirector of the Borderlands Program at the Coronkite School of Journalism at Arizona State University, and the border-Mexico correspondent for the Dallas Morning News. He is currently writing his second book, Shadows at Dawn. @ajcorchado