by Ruben Navarrette

Education isn’t limited to schools – it starts at home. What should parents do to be leaders in their children’s lives and inspire educational achievement?

Americans have spent decades mulling over the concepts of parents as providers, friends, role models. But here’s a new idea — one that perhaps isn’t so new after all: parents as leaders.

We can take that to mean, leaders in their community and in society as a whole. But also, more importantly, we should take it to mean leaders in their children’s lives and the role that education will play in them. If they get that second part right, parents will enrich the country, improve society as a whole, and maybe even make a better world.

So what can parents do — and what should they do — in these busy and hectic times to be leaders in their children’s lives and lead those who look up to them toward academic achievement, professional success, and personal fulfillment?

For one Mexican-American father in Central California — who, by the way, also happens to be an educator with an inspiring life story — the goal isn’t just to teach his own children how to navigate the world they live in. That would be enough for many parents, but it’s not sufficient for this one. Rather, his goal is to encourage his children to discover and explore new worlds they could never have dreamed of.

Stories like this matter because demographics are destiny. Latinos are America’s largest minority. Given that they make up 17 percent of the U.S. population, and represent one out of four kindergarten students, it’s time to take a hard look at this population. In fact, it’s impossible to go about the difficult work of reforming America’s public schools and increasing accountability in education without improving the education of Latino students.

But are we finally willing to admit that the education process doesn’t just happen at school, but that much of it takes place in the home? That is especially true for Latinos, for whom the most beloved and valuable institution is the family.

Planting the seeds of education

Martin Mares learned this lesson first-hand years ago while growing up in Central California’s San Joaquin Valley. It’s there that his family settled, far from the Mexican state of Jalisco, where his grandfather boarded a train to Los Angeles in 1898 when the family patriarch was only 12 years old.

As it did with so many other clans from Texas to Oklahoma to Missouri, the Valley lured the Mares family with its promise of a endless supply of field work. Martin’s parents worked all their lives as farmworkers, picking fruits and vegetables. As one of eight children, seven of whom went on to earn bachelor’s degrees, Martin remembers, as a boy, helping his dad take off his boots at the end of a long and exhausting day.

“My dad only went to school until the third grade, but he valued education,” Mares told me. “He would tell me, in Spanish, don’t be a burro like me, you have to go to college.”

“My dad only went to school until the third grade, but he valued education,” Mares told me. “He would tell me, in Spanish, don’t be a burro like me, you have to go to college.”

The boy nodded his head, even though he really didn’t know what it meant to go to college, other than college was “a place with a lot of books where you become a secretary or a teacher.

But his life changed when he caught his first glimpse of a university campus during a school-sponsored tour of California State University-Fresno in the 7th grade. One look at the buildings, fountains, and libraries and he was hooked.

Mares went on to attend and graduate from that same university, with the intention of joining the business world. Even when he decided to become a teacher, he intended to stay in the classroom for only two years before going on to another profession.

Instead, he was chosen to go onto a track to become an administrator and eventually, after earning a masters’ degree, worked as a vice principal and principal at elementary, intermediate, and secondary schools in the same school district that he attended as a student — Parlier Unified, just southeast of Fresno.

Inspiring dreams of ivy-covered walls

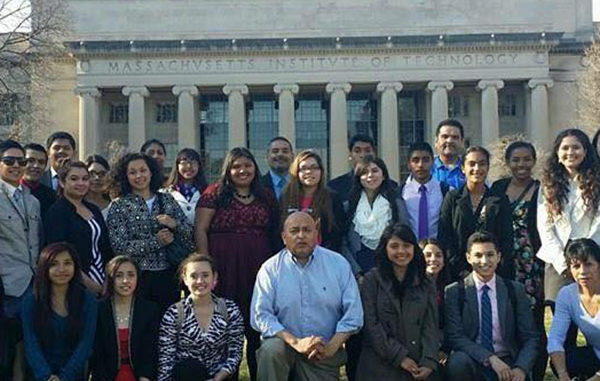

Now the district’s chief academic officer in charge of college and career readiness, Mares is also the founder and executive director of the Ivy League Project, which he started in 1992.

That year, during spring break, he took six high school students on a very special “field trip” to visit a handful of Ivy League schools including Harvard, Yale, Princeton and Columbia. Designed for students who are economically-disadvantaged and often from immigrant households, where they would be the first to attend college, the idea was to open up the kids’ sense of possibility and inspire them to do well enough academically that they could be admitted to such a high-caliber university.

Now in its 24th year, the Ivy League Project takes 45 students each year to visit nearly a dozen colleges and universities, including all eight Ivy League schools and other prestigious institutions like Georgetown and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In all, the program, which has now expanded beyond California and operates in Texas and Arizona, has seen 1,500 of its alumni admitted to public universities, and 256 admitted to the Ivy League.

Leadership begins at home

At home, along with his wife, Sulema, who is also an educator, Martin is busy raising three children of his own — Andres, 16, Jacqui, 14, and Isabella, 9. Education is a constant theme, and college a common topic of discussion in the home.

“Our kids look at Ivies and the University of California,” he said. “My wife was pregnant, when we found ourselves touring Stanford. You could say that our son, Andres, visited his first university in the womb.”

Mares involves his children in all aspects of the Ivy League Project, in order to expose them to his labor of love. “They had to go to my Ivy League meetings on Saturday,” he recalled. “They got to meet all the superstar kids in Central California, and eventually go on the trip.”

He and his wife are thinking about sending Jacqui to an elite boarding school in New England, to prepare her for college. It’ll cost $8,000, and the family will have to stretch a little to afford it. But, for the Mares household, these sorts of things are considered sound investments.

For his part, Mares remembers what his parents considered an extravagant outing. It was a trip to a local outdoor mall. “We would get dressed up, and, when we got there, we’d see people of different races and backgrounds,” he said.

Now, like the Ivy League Project he started, Mares’ child rearing makes sense. “I want to expose my kids so they can see different cultures and visit different lands and meet different people,” he said. “That’s how you learn.”

Finally, I asked, what sort of things does he do to take a leadership role in the everyday lives of his children? He was ready with an answer.

“I put motivational quotes in lunch boxes, send them texts, attend back to school nights, get course syllabuses, recommend books, monitor tests,” he said. “I take them aside, and have breakfast with them individually. I make sure they know what they need to do to get where they want to go. As a parent, you have to stay on top on it.”

Efforts like this may not garner headlines, but it is through the unseen leadership of parents like Martin Mares that generations of Americans, of all cultures and backgrounds, are prepared for the world that awaits them. And Mares is absolutely right: Parenting is the most difficult, most satisfying, and most important job we will ever have, and how we do it will be on display — through our children — long after we’re gone.

Parenting doesn’t come with a manual or a roadmap. But, done correctly, it can change lives, shape generations and make the world a better place.

Parenting doesn’t come with a manual or a roadmap. But, done correctly, it can change lives, shape generations and make the world a better place.

If that’s not leadership, then nothing is.

Ruben Navarrette Washington Post Writers Group syndicated columnist, contributor to the Daily Beast, and George W. Bush Institute Fellow.

This essay was originally published at The Catalyst. The Catalyst is a quarterly publication from the George W. Bush Institute that operates from the belief that ideas matter. They shape public policies, spur action and lead to results.