by Asma Khalid, NPR

It used to be that when political experts would pontificate about “Latinos” in Florida, they were talking about Cubans. But those days are over. There are now more than one million Puerto Ricans in Florida (1,006,542 to be exact).

The reason all this migration is important politically is that Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens, so they can register to vote as soon as they step foot on mainland soil. And, many of them are choosing to settle in central Florida — historically, the swing region of this swing state.

(Residents of Puerto Rico and other U.S. territories cannot vote in the November presidential election).

Betsy Franceschini remembers how rare it felt to find a fellow Puerto Rican in Orlando when her parents moved here in 1979.

“I remember my father getting real excited when in Kmart somebody would speak Spanish and he was like ‘oh my God, there’s somebody here that speaks Spanish,’” recalled Franceschini, regional director for the Puerto Rico Federal Affairs Administration.

Nowadays, you can walk up to a lechonera and order Puerto Rican-style pork and rice in Spanish. Then drive down the road, and attend church services in Spanish. And then, drive a little further and pick up groceries at the Publix Sabor — all in Spanish.

But, in addition to changing the food and the culture around here, Puerto Ricans have the potential to change the politics.

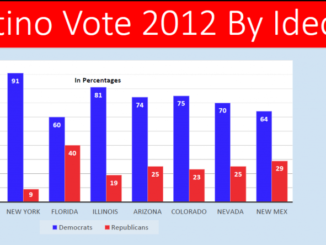

A majority of Puerto Ricans identify with the Democratic party — 57 percent; that compares to just 22 percent who lean Republican, according to data from the Pew Research Center.

But, Franceschini said, she’s noticing an interesting trend among the new arrivals.

“There is a great amount of Puerto Ricans that are registered independent,” she said.

And, that means both Democrats and Republicans are trying to reach them.

“Puerto Ricans in central Florida are voting majority Democrat. Now what you’re starting to see is the Republican party introduce their economic message to the Puerto Rican population,” explained GOP political analyst Frank Torres. “The barricade between Republicans making progress is immigration,” he added, “Puerto Ricans don’t fall underneath the immigration umbrella but they see that relationship and how it’s being handled by the GOP as sort of a hint of the way other policies would be handled by that party.”

The toxic immigration rhetoric is a risk even conservative Latino activists realize.

“Puerto Ricans — they feel like they are immigrants in their own country,” explained David Velazquez, deputy Florida director of the conservative LIBRE Initiative, an organization funded by the Koch Brothers.

Turning an economic exodus into political victory

So Velazquez and the LIBRE Initiative are trying to focus on economic policies. They’re not pitching a particular candidate; instead, they’re playing the long game — knocking on doors in high population Hispanic areas and offering services like English classes or financial literacy courses, while selling a message.

“We think that a limited government equals more opportunities for people to start a business to rise up and have success in the country,” explained Velazquez, as he knocked on doors in the overwhelmingly Puerto Rican neighborhood of Buenaventura Lakes in Osceola County.

And, that philosophy is resonating with some Puerto Ricans, like Juan Salgado.

“I like the Republicans, cause I prefer small government,” said Salgado, who moved to Orlando two years ago.

Salgado is a lawyer by training, but it’s been hard to find a steady professional job in Florida.

“I used to work in the U.S. post office, but it was a contract,” said Salgado “After February, they cut the contract, so right now, I’m unemployed.”

Salgado says the number one issue for him this election is the economy, but he’s also deeply concerned about a more unique problem.

“I’m really worried about the situation in Puerto Rico,” he said. “It’s really bad.”

Salgado says if a candidate came up with a solution to Puerto Rico’s economic crisis, he would be more inclined to vote for him.

His old law school classmate from the island, Phillip Arroyo, agrees Puerto Rico needs financial help — but he’s skeptical Republicans will offer an answer.

“The Republican party is totally anti-Latino, anti-minority, that’s not an exaggeration these days with Donald Trump’s crusade of ignorance,” Arroyo said.

Arroyo moved to Orlando last year, and he’s been a Democrat for years. He chaired the Young Democrats of America chapter on the island.

“I can see the inequality in terms of the way the Puerto Ricans on the island are treated and the way Puerto Ricans here are treated,” Arroyo said.

Arroyo wants more than a short-term economic solution to Puerto Rico’s debt problems, he wants a political solution. He says it feels like the island is stuck in a colonial relationship, and his priority this election is a change in Puerto Rico’s political status.

“The fact that Puerto Ricans [on the island] can’t vote for president, do not have equal representation, I think it’s a disgrace,” said Arroyo. “Puerto Rico is deprived of the democracy that’s preached here,” he added.

Arroyo is frustrated that the 2012 referendum calling for statehood was ignored.

“If you’re not willing to give Puerto Rico full equal rights, give them independence, but don’t exploit them,” he said.

Voter education

There’s a realization from both parties that Puerto Ricans will be important on election day, and there are big efforts underway to register them to vote.

On a recent weekend, Mi Familia Vota co-sponsored a social services fair for newly arrived Puerto Ricans. Families could enroll in health care, learn about job opportunities, and, of course, register to vote.

Just after signing up to vote, Tatiana Cesario, 24, said she didn’t choose a political party; in fact, she doesn’t know much about any of the candidates, and isn’t even sure if she’ll vote. Cesario moved to Florida in June with hopes of becoming a flight attendant.

Her political situation may illustrate one of the biggest hurdles for newcomers — basic voter education. Puerto Rico has completely different political parties, local elections are held only once every four years, and election day is a public holiday.

“In Puerto Rico, politics is a fiesta,” said Rafael Benitez, a Democratic activist, “There are caravans, there is music. And, here, here, you don’t have that, you don’t have that fervor.”

Benitez wants to recreate that fervor — caravans and all — come election day in Orlando; he’s convinced Puerto Ricans are natural Democrats.

“We have a long way to go, but if we could get registered and ready to vote, I’d say half of the Puerto Ricans that are here, I think that it will greatly benefit the Democratic party,” said Benite