by Carolyn Phenicie

About one-third of American 4-year-olds were enrolled in state-funded preschool programs in 2017, a sharp increase from the 14 percent enrolled in 2002, though spending on those programs and their quality hasn’t necessarily kept pace, a new report finds.

Enrollment is growing, but not fast enough, and it shouldn’t come at the expense of quality, said Steven Barnett, senior co-director of the National Institute for Early Education Research, which released its annual “State of Preschool” report Wednesday.

Eleven states meet fewer than half of the institute’s 10 quality benchmarks, including factors like maximum class sizes and mandatory degrees and professional development for teachers. Those states include Texas, Florida, and California, which enroll some of the largest numbers of preschoolers.

“Quality trumps quantity. There’s no point in spending money to give kids a program that doesn’t help them,” Barnett said on a call with reporters Tuesday.

What is “most distressing” is states’ tendency to trade quality for quantity — and they aren’t even adding seats that quickly, he said.

“It’s going to take us a very, very long time … at the current pace to reach every child in every state, and yet we don’t prioritize quality to ensure that programs are highly effective for kids,” he said.

States should choose a “date certain” by which they’ll have a set percentage of young children in high-quality programming, and then work smoothly toward it, Barnett said. It is possible to expand enrollment quickly while maintaining quality, he said, pointing to Alabama and New York City as recent examples.

Research has shown that high-quality preschool programs can boost academic achievement and lead to better life outcomes, like greater education and less incarceration.

It’s more important than ever for states to take the lead on ensuring the existence of quality preschool programs, as the federal government takes a backseat through the Every Student Succeeds Act, Barnett said.

ESSA also allows districts to use their federal Title I dollars targeted toward low-income students for preschool, Carey Wright, Mississippi state superintendent of education, said on the call with reporters. It’s been a big source of funding as her state expands the pre-K program it started four years ago, she added.

Funding, key to maintaining and improving quality, has also decreased over the years. States spent an average of $5,005 per child in 2017, slightly less than they did last year, and nearly $400 less than they did in 2002 when adjusted for inflation.

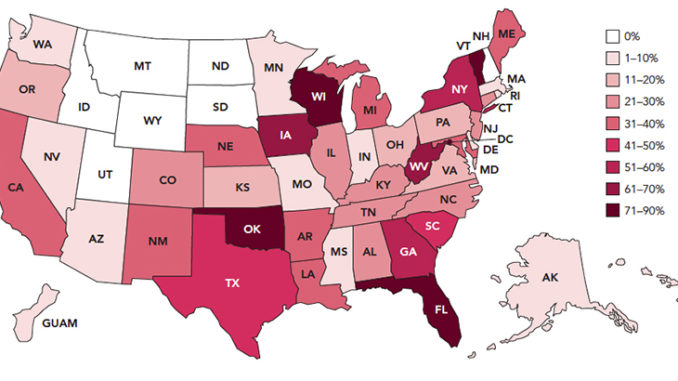

Like much in education, access to and quality of pre-K programs varies widely across the states.

Source: “State of Preschool 2017” report from National Institute for Early Education Research.

Nine states and Washington, D.C., serve more than half of 4-year-olds, but eight states have no state-funded program at all. On funding, it varies, from D.C., which spends nearly $17,000 per student, to Nebraska, which spends less than $2,000.

Though pre-K is primarily in state leaders’ hands, the federal government can influence the offerings, for example, by increasing funding for Head Start programs and continuing to fund Preschool Development Grants, which have been essential to many states starting or expanding pre-K programs.

“The federal government has a critical role to play here. They can set the tone. They can provide seed funding that helps show progress,” Mark Shriver, president of Save the Children Action Network, said on the call.

The report also looked at how preschool programs are serving dual language learners, and found that they largely need improvement.

Three states with big populations of English language learners — Arizona, Florida, and New York — don’t even know the home language of the preschool children they serve.

Those students have a “double task” of language development in two tongues, Barnett said.

“We know that dual language learners are a group that makes the largest gains from attending high-quality preschool, at the same time they’re at elevated risk of school failure,” he added.

Carolyn Phenicie is a senior writer at The 74 based in Washington, D.C., covering federal policy, Congress, and the Education Department.