by Kevin Mahnken, The 74

As Congress debates whether to approve a long-term extension of the Children’s Health Insurance Program, a recently released brief from the Urban Institute has spotlighted the initiative’s importance to young families. Nearly half of all American children under the age of 4 receive health care coverage under CHIP or Medicaid, along with 20 percent of their parents.

CHIP covers 8.9 million children nationwide whose families, though poor, fall above the income threshold for Medicaid. After last being extended in 2015, the program’s federal funding ran out in September. Though it has historically enjoyed bipartisan support, partisan divisions over how to pay for another extension blossomed into a major political dispute in December.

Although a short-term provision was passed before Christmas providing an additional $3 billion through the end of March, many states are projected to face shortfalls in their individual CHIP programs that will lead to cutbacks. National lawmakers now face calls from across the political spectrum — including, most recently, Hillary Clinton — to reach a more lasting agreement.

In a paper for the Urban Institute, researchers tallied the number of parents and children in all 50 states who turn to CHIP and Medicaid for medical insurance. The two programs are typically paired in analyses of this type because of CHIP’s program design: States are permitted to dedicate federal dollars to either establish their own CHIP programs or else simply expand their statewide Medicaid systems. The national breakdown between the two approaches is roughly 50–50.

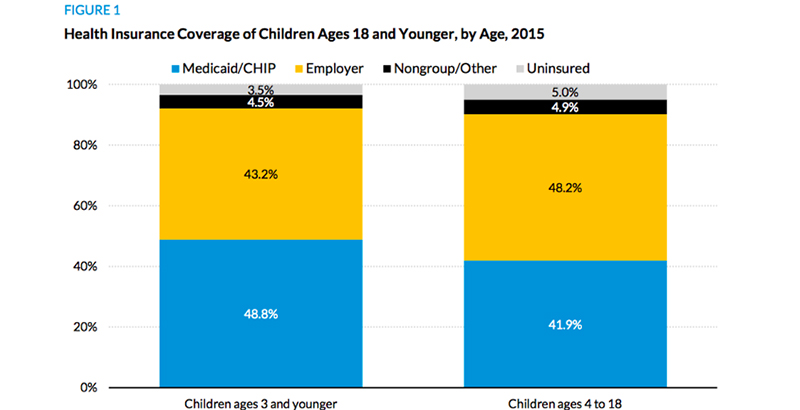

While huge numbers of families rely on both programs for insurance coverage, those with newborns and toddlers are uniquely dependent upon them. Roughly 42 percent of kids between the ages of 4 and 18 are insured through Medicaid and CHIP, compared with nearly 49 percent of those under the age of 4. About 1 in 6 parents of older children is covered under the two programs, while 1 in 5 parents of younger children is.

The coverage provided under Medicaid and CHIP includes early preventive treatments for physical and cognitive problems that are more pronounced in low-income patients and often grow worse with the passage of time. Receiving care before a child’s fourth birthday can pay dividends years into the future.

“Vision, dental, behavioral, and developmental screenings and appropriate follow-up care and treatment can set young children up for better health and functioning in childhood, making Medicaid/CHIP a critical link to children’s readiness for school,” the authors write.

For children already enrolled in school, publicly financed health insurance remains critical. Many states deploy Medicaid funds to schools, where they underwrite everything from mental health counseling to occupational therapy to hearing tests. When Republicans were considering bills to repeal Obamacare and substantially reduce Medicaid funding last summer, health care analysts projected that millions of children could be cut off from much-needed care. Now many fear that even a short-term expiration of CHIP funds could carry the same risk.

Years of research have shown that access to medical care, especially in the early years, improves life outcomes for low-income children in realms far beyond personal health. A 2014 paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that a 10 percentage point increase in Medicaid eligibility between birth and age 17 cuts the likelihood of not completing high school by as much of 6 percent and boosts the four-year college completion rate by 2.3–3 percent.

“Our estimates suggest that the long-run returns to providing health insurance access to children are larger than just the short-run gains in health status,” the authors write, “and that part of the return to these expansions is a potential reduction in inequality and higher economic growth that stems from the creation of a more skilled workforce.”