by Kimberly Breier

The bigger picture of this week’s events in Mexico—namely, the meeting of Republican nominee Donald Trump and Mexican President Peña Nieto—is that it serves to highlight the importance of the U.S.-Mexico bilateral relationship to both countries and underscores the need for serious policy focus on the relationship. As we discuss the immediate, we should not lose sight of the fact that this year’s focus on Mexico more broadly presents an opportunity to reframe the bilateral relationship in a new light, with a new strategy.

It is well-known within the halls of government that the United States’ relationship with Mexico is one of the most important—and the most complex—that policymakers encounter. Those new to Mexico policy often find that the breadth and depth of the bilateral relationship is daunting, as it can range from trade to health to transboundary water management in a single day. It is hard to name a U.S. Cabinet office that does not engage regularly with its Mexican counterparts—from the usual foreign policy offices to the more domestically focused agencies. This mix of foreign policy and domestic policy long ago sparked the use of the term “intermestic” to describe the relationship. It is exactly so, a complex mix of international and domestic policy with all of the overlapping and sometimes contradictory impulses that implies.

While foreign policy is the purview of the U.S. federal government on paper, the relationship with Mexico both follows that rule and diverges from it. An added level of complexity comes from the fact that the economic and social integration between our two countries is such that many U.S. states and cities have developed their own deep and dynamic ties with the Mexican federal government and counterpart states and localities across the border. An average U.S. citizen who resides along the border and U.S. businesses even far from the border are involved with Mexico regularly. With millions of legal Mexican immigrants and their families, along with the illegal migrant population, the daily interactions with Mexico are deep and diverse.

Despite the general understanding that Mexico policy is important and complex, U.S. policy toward Mexico very often lacks a coherent strategy that recognizes both the breadth and depth of issues that matter greatly to the United States and to the American population—from economic security and trade to national security (counterterrorism, counterdrugs, etc.), immigration, health, the environment, and many others. Mexico policy is unusual foreign policy in this sense—it is not some abstract idea concerning a country far away that is largely perceived by Americans as not being important to their lives. Mexico policy is immediate. Partly for this reason and partly because of domestic politics, U.S. policy toward Mexico can often be reactive to daily events and news cycles. In some cases, it is not really a policy at all, but rather a series of public statements on bilateral topics of the day.

The Road Ahead

Improvisation is not a recipe for good policy and does not solve problems, it tends to perpetuate them. The conversation with Mexico is one that must be conducted, going forward, with a strategic approach to what the bilateral relationship actually is and a serious vision for where it can go. Absent a vision, the relationship will devolve, as it often does, into tit-for-tat exchanges on topics on which we disagree or in reaction to the daily news and domestic politics on both sides.

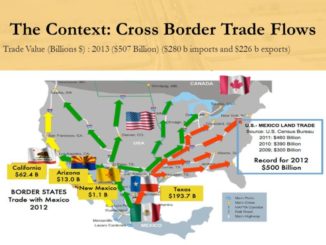

The massive volume—roughly $600 billion per year—of trade between the United States and Mexico places Mexico as the United States’ second or third largest trading partner depending on the year. We trade in cars and parts, machinery, minerals, plastics, agricultural products, processed foods and beverages, aerospace, electronics, textiles, and just about anything else one can think of. Beyond buying and selling there are many products we make together. This intense and powerful trading and integrated supply chain relationship involves not only border states, but even U.S. states distant far from the border that are not normally perceived as having a close relationship with Mexico, even though the data show significant trade volumes. The economic relationship is fundamental to the economy and the consumer lifestyle to which Americans have become accustomed. Goods are less expensive and more widely available to Americans in part because of this relationship. We can discuss the net effects of trade policy and the costs and benefits for Americans, and we should, but in the context of the broader bilateral relationship with all of its assets and flaws, and in an environment of realistic policy options.

One point often lost in the conduct of policy toward Mexico is that on any given day, there are perceived “wins” and “losses”—that is, things that the two countries are doing well, and those areas where cooperation is insufficient, is hampered by mistrust, or is otherwise flawed. This reality makes it all the more critical that policymakers are aware of the totality of the relationship, are clear on U.S. priorities, and reflect that in dealings with Mexico.

Illegal immigration has been a key challenge in the bilateral relationship for a generation and is a prime example of a policy discussion that tends to be reactionary. Current trends in immigration from Mexico, according to recent studies from the Pew Research Center, show a net-reverse in total Mexican migration to the United States. That is, since 2009 more Mexicans have left the United States than are coming to it. Why? No serious answer to the challenges that illegal immigration poses can be found without looking at the drivers of immigration from Mexico, and the role that trade policy and the broader economic relationship play in influencing migratory flows. We have two countries living next door to each other, with one having a GDP per capita that is more than six times the other, on average. It stands to reason that there could be migratory flows from the lower income per capita country to the higher one. This is not a challenge solved overnight; there are no quick fixes and the approach must be joint and comprehensive.

Improved border security can be part of the answer, perhaps in the short-term, and one that any sovereign state can and should implement. Improved border security is also something that can be done cooperatively, and not just unilaterally. The U.S. southern border is, in fact, more secure when Mexico helps to deal with threats of all kinds before they get there—Mexico of course, does this in many areas every day. The most recent example relates to the flows of third-country migrants via Mexico from Central America. There is much more that can be done, but we need to begin the conversation by recognizing the cooperation we already have on border issues and identify areas where cooperation is a force multiplier. In the long run, however, improved border security addresses a symptom of the problem and not the cause. Border security alone is not likely to be an effective, long-term solution to the complex challenge of illegal immigration.

Vision Needed

The bilateral relationship with Mexico needs to evolve, just as global dynamics have. The relationship needs a new, high-level shared vision for where we need to go and how to get there. One focus should be continuing to envision the border as the last line of defense, not the forward guard for dealing with our challenges. On the commercial side, the two governments are already working together on policies that implicitly recognize that security can be addressed away from the border in order to prevent bottlenecks, increase efficiency, and make the goods we produce together more competitive in the global economy. Pre-clearance of people and cargo and the use of new technology is changing the way we “do the border” on the economic side of the relationship—while also improving security and efficiency. It is a joint vision like this that moves us forward and could be applied across the spectrum.

The same framework applies to more traditional national security issues, such as counterterrorism, counterdrugs, and counter-trafficking. Mexico is a rarely discussed, but critically important, partner on these national security issues. Cooperation with Mexico on these issues puts the United States on the offense, helping us catch threats early, before they reach the border. Policymakers on both sides know there is a lot more that can be done to adapt to evolving threats and that current efforts certainly fall short. While there is much room for improvement, and in particular for building trust, it will not happen by accident and in a reactionary policy environment. Wide-ranging security cooperation has to be a willful, bilateral commitment to joint effort with agreed priorities. That is, we need a strategy, and one that acknowledges and addresses the security concerns of both countries.

Little discussed in the news are issues like health and environment that do not obey the line that marks the border between the United States and Mexico. If the threat of the Zika virus increases as many experts fear it will, Mexico will be a critical partner of the United States, where the two countries will need to have a fluid flow of data about the spread of the virus and containment. We have been through this before, on avian influenza and other outbreaks. Environmental issues, too, including climate change and water management are critical bilateral issues that do not recognize national borders. Having a partner and ally on these issues is far preferable to the alternative when two countries share parts of the same continent.

The list of issues goes on and on and the need for a thoughtful strategy is compelling. On any given day, any issue can emerge as an irritant in the bilateral relationship and if the countries had an overall shared strategy, the relationship in all areas can weather the storm and find constructive solutions. The shared vision helps to insulate the relationship from the inevitable ups and downs.

Should We Consider a New Structure?

The Mexican and U.S. governments (and also Canada from time to time) have long toyed with the idea of creating a special structure of some kind—an office or appointee charged with overseeing the bilateral relationship or the tri-lateral North American relationship including Canada, at the highest level. The idea has been to create a structure within each government with an institutional memory that would transcend changes in leadership and political party in each country and keep the bilateral relationship on course. The idea is not to create a supra-national structure, but rather to designate a coordination point person within each sovereign state. Given the critical moment we find ourselves in, it is probably the right moment to have this discussion again.

The U.S. candidates’ transition teams should be thinking through the pros and cons of the appointment of a high-level official, with the president’s full confidence and domestic political savvy, that could be the sherpa (the term used for the NSC official that oversees preparations for major international economic meetings) for a new strategy toward Mexico. Another previous formula used in the Americas that could be considered is the structure of the office of a special envoy. The mission of the new appointee would be to oversee the new strategy and the totality of the Mexico relationship, both its foreign and domestic aspects, working with all of the critical stakeholders from U.S. federal offices, governors, states, and localities to guide, inform, and coordinate key aspects of the relationship.

Some, myself included, have resisted the creation of another government office as the answer, arguing that the office already exists and is called the Department of State. History, however, may be urging us to reconsider. The Mexico relationship is uniquely complex and perhaps the moment has arrived for a more formal recognition of that fact.

The candidate who takes the oath of office in January 2017 in the United States should be prepared to engage with Mexico in a serious, comprehensive way with a clear strategy to address our shared challenges. From this year’s adversity comes opportunity. The next U.S. president should place Mexico policy near the top of the priority list—and keep it there.

.

Kimberly Breier is the director of the U.S.-Mexico Futures Initiative and the deputy director of the Americas Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C.

.