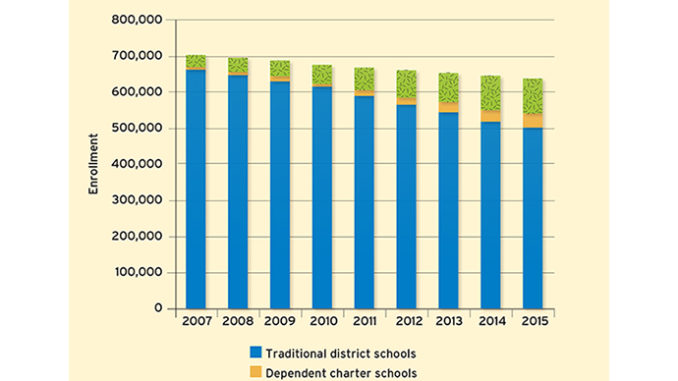

Throughout the 1990s and well into the new millennium, the massive Los Angeles Unified School District barely noticed the many charter schools that were springing up around the metropolis. But Los Angeles parents certainly took notice, and started enrolling their children. In 2008, five charter-management organizations announced plans to dramatically expand their school portfolios, and now more than 100,000 L.A. students attend independent charters (see Figure 1). Another 40,000 students are enrolled in dependent charters, which are created by the district and considered part of the district’s portfolio of schools.

Many people, including some wealthy philanthropists, are eager to accelerate that growth, while the district—and the teachers union—want to rein it in. The conflict between the two camps has polarized not just families and educators but the entire city. And last fall, after someone leaked a private multimillion-dollar plan to vastly expand the number of charter schools in the district, the hostilities rose to new heights.

L.A. Unified, with an enrollment of 550,000, is the nation’s second-largest school district, behind only New York City. The district sprawls over 720 square miles, more than half the size of Rhode Island. It includes not only the city of Los Angeles but 31 smaller municipalities as well. The only glue holding it all together is a web of clogged interstate freeways.

As spectacular as its sprawl is the size of its debt. L.A. Unified is saddled with $13 billion in unfunded pension and health-care-benefit liabilities. The district is one of the very few that still offers retirees and their dependents lifetime medical coverage. Because it has failed to set aside adequate funds to cover the costs involved, the district has no choice but to tap into its operating budget. The operating deficit, projected at $333 million for 2017–18, could exceed half a billion dollars by 2019–20 (see Figure 2).

So far, the district has failed to take decisive action toward putting its financial house in order. Although it has lost 100,000 students since 2006, the district has actually added teachers and other employees: the administrative staff grew 22 percent over the past five years, according to a district report released in May. With the decline in enrollment has come a drop in revenues: state aid is based on the number of students attending a district’s schools.

Half of the enrollment decline stems from the rising popularity of the district’s 228 independent charter schools. The other half has resulted from other factors: parents enrolling their children in private schools, families moving out of the city, and a decline in the birthrate. Although champions of the district insist that charter schools are draining money—and some of the strongest students—from traditional schools, critics say the district’s focus on charters is merely a strategic attempt to distract public attention from its own financial mismanagement.

When charters were first authorized by law in California in 1992, nobody—not school superintendents, not union leaders, not even charter advocates—imagined they would grow to their current scale: 1,230 schools statewide, with 80 new schools opened in the 2015–16 school year. L.A. has more charter schools than any district in the country. If you count dependent charters, the total rises from 228 schools to 282, representing 23 percent of the student population.

The waitlist for those 282 charter schools: 41,830 students.

The city’s charter schools are popular because many of them are very good. Multiple studies suggest that L.A. charters are among the best in the nation at helping low-income minority students succeed in school (see Figure 3). The most thorough research comes from Stanford’s Center for Research on Education Outcomes, which in 2014 concluded that L.A. charter-school students, on average, gained the equivalent of 50 additional days of learning per year in reading and 79 additional days in math, compared to district school students.

Over the past decade, the performance of L.A. students on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, the nation’s report card, has risen, narrowing gaps with the California average and the average for large cities nationwide (see Figure 4). However, the performance of charter-school students on the NAEP far outstrips that of students in district schools. And the fiscal challenges now facing the district, and the resulting political turmoil, threaten the continuation of that progress.

Escalating Tensions

Last fall, the conflict between charter and district schools intensified after someone leaked a plan from the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation to raise up to $490 million from foundations and wealthy individuals to double the number of charter schools in the city, with the goal of enrolling about half the students in the district within eight years. The proposal had to be taken seriously, since it came from the billionaire Eli Broad, who built two Fortune 500 companies and became L.A.’s most prominent philanthropist. A patron of the arts, medicine, and education, Broad has invested nearly $600 million in education over the past 15 years, supporting a mix of traditional and charter schools.

When the Los Angeles Times leaked details of the draft plan in August and September 2015, the news set off a community-wide crisis that roiled for months. The union, United Teachers Los Angeles (UTLA), staged protests and crafted an effigy of Broad. Several L.A. Unified school-board members denounced the plan, and member Scott Schmerelson asked the board to adopt a resolution officially opposing it.

The union, led by Alex Caputo-Pearl, immediately seized upon the public relations opportunity to pursue the national anti-charter theme of billionaires trying to privatize public schools. (It didn’t help that the report was replete with corporate terms such as “market share,” “strategic messaging,” and “proof points.”) On its website, the union posted an unflattering photograph of Broad (pronounced “brode”) with the headline “Billionaires Must Stop” superimposed on a red stop sign. Below Broad’s photo, the caption leads off with: “Hit the Road, Broad.”

Elected in 2014, union chief Caputo-Pearl is widely respected by both supporters and opponents as a talented organizer, the likes of which this city has never seen. (Caputo-Pearl did not respond to my requests for an interview.) His efforts were welcomed by L.A. Unified supporters and charter critics. “When that [plan] leaked, everyone was shocked,” said Scott Folsom, a former PTA president in L.A. and longtime district watcher. “Eli Broad and a group of charters taking over half the district? What happens to the other half, the half that don’t get taken over?”

Folsom echoed the oft-heard criticism that charters siphon off the top students, and the children of the more-motivated parents, from the public schools. “Charters cherry-pick by taking the most aggressive, frustrated, and interested of those parents and make the promise that their kids will do better at a charter school,” he said. California charter advocates, however, point to multiple studies indicating that so-called cherry-picking does not account for the higher test scores seen among charter students.

Caputo-Pearl’s goals mesh well with those of the district, and based on recent headlines, it would appear that the war against charters is succeeding in directing attention away from declining enrollment and rising debt.

Who leaked the report that ran the Broad plan off the tracks for a year? Times reporter Howard Blume won’t say, but given the large number of union sympathizers and others who received advance copies, one might well ask: Who didn’t leak it?

Troubles upon Troubles

Tensions around co-location—the practice of housing charter schools and district schools in the same facility—ramped up after the draft plan became public.

The co-location initiative began in 2000 when California voters approved Proposition 39, which mandated that district facilities be “shared fairly among public school pupils, including those in charter schools,” and that districts provide charters with facilities that were “reasonably equivalent” to those given to district schools. Charter leaders say they supported the proposition on the assumption that school districts would treat their students equitably, as stated in the law. But from this perspective, L.A. Unified never complied, leading to lawsuits filed by the California Charter Schools Association to force co-locations (full disclosure: I have a daughter who works for CCSA). Each side of the conflict mobilized its parent allies.

Often, one side would accuse the other of falsely claiming they needed a larger facility, or one side would identify empty rooms that the other side would say were needed as art rooms, music rooms, teachers’ collaboration rooms, and so on.

From the perspective of L.A. Unified supporters, Proposition 39 was a Trojan horse. Its main purpose was to make it easier to pass bond issues for public school funding, and district advocates say that most voters were not aware of the provision (“buried in a little Easter egg,” as Folsom put it) requiring public schools to offer charters their unused space.

Folsom said that the magnet schools in the district manage to share space with charters without friction, but that charters forcing their way into other schools created an “us-versus-them” mentality.

As a result, the charters are feeling the heat, especially during “walk-ins” organized by the union, where students, parents, and teachers have protested charter expansion. One sign carried by a protester at one of these events implored: “Billionaires, have a heart. Your plan will tear our schools apart!” When I visited one of the Equitas charter schools in the spring, I learned that their schools had seen three demonstrations in just one week. One morning a group of parents filed into the flagship school, asked to fill out paperwork for enrolling their children, and then suddenly leaped into demonstration mode, pulling leaflets from their pockets. Interestingly, all the parents were wearing yellow visitor ID tags issued by a local L.A. Unified middle school.

The issue? The possibility that Equitas charters might claim some empty classrooms in their school. (Equitas founder Malka Borrego said she has no interest in their space.)

Another incident occurred in the spring at Community Preparatory Academy (CPA), a charter that shares space with Ambler Avenue Elementary in Carson, a city of 90,000-plus people. CPA co-leader Maisha Riley arrived at the school on May 4 to find posters hanging face in on the perimeter fence bearing legends such as, “We Can’t Grow, So Charter Must Go” and “It’s Not Fair That We Have to Share.”

Inside the elementary school, students had written graffiti in the bathrooms: “F— CPA.” Riley said that on the first day of school, the Ambler principal had told her, “We don’t like charters. We don’t want you on our campus.” Riley’s students, she said, are frequently bullied by the district-school kids.

When Riley asked around, she identified the protest instigator as a 5th-grade teacher at Ambler who during the 2015–16 school year was also the UTLA union rep at the school. Far more revealing: that same teacher had been tapped by her principal to serve as the school’s liaison to the charter.

The district appears to have minimal interest in changing the dynamic between the two schools. After the incident, the district sent out a representative to conduct assemblies for the students to discuss “commonalities,” said Riley, who characterized the meetings as “fluffy and nice,” but added, “A lot of the bullying that was going on is still going on.” Riley asked for a new liaison (“A lot of the bullies came from her class, and she was the one putting up the signs. I didn’t see her as a neutral party”) but was turned down. That was the prerogative of the Ambler principal, she was told. Neither the Ambler principal nor the 5th-grade teacher returned calls.

The Carson confrontation offers an insight into famously laid-back L.A. The only press coverage of the incident was a local public-radio station report, which didn’t mention the dual roles of the Ambler teacher. In New York City, such an event would probably draw prominent coverage in the tabloids, complete with photos of the bathroom graffiti and perhaps accompanied by an editorial. The same holds true for the deficit issue, which has not received frequent or regular coverage in the media.

Charters Expand

L.A. Unified has been losing students at a rapid clip since 2008, when five charter-management organizations—Green Dot, Aspire, Partnerships to Uplift Communities (PUC), Alliance College-Ready Public Schools, and Inner City Education Foundation Public Schools (ICEF)—announced major expansion plans. Everything changed when these big operators made it clear they were going for scale, thus challenging L.A. Unified for huge numbers of students. Suddenly, school board members became identified as “pro-” or “anti-” charter.

“Until those five big CMOs made the announcement of big plans for growth, serving a significant portion of the low-income population in Los Angeles, I didn’t feel anybody was really paying attention to us,” said Marco Petruzzi, who oversees Green Dot Public Schools National. Green Dot’s California network operates 18 charters in the city.

By 2011, the school district had geared up for battle, mostly by making life miserable for the charters. Almost overnight, the paperwork demands on charters exploded. What were once routine charter renewals became ordeals.

A representative of one large charter operator, who asked to remain anonymous, said its schools were filing a thousand pages of accountability paperwork per school per year, employing the equivalent of five people working full-time on that task.

After the Broad plan was leaked in 2015, L.A. charters also got stung with a series of rejections from the board. In February 2016, CCSA published an “open letter” from charter leaders to the district’s board: “While two years ago the L.A. Unified Board of Education approved 89 percent of new charter school petitions, so far this year the board has approved just 45 percent. This decline is dramatic. Given that charter schools are continually gaining more experience and sophistication, it is difficult for us to understand why and how the district finds charter petitions so much less credible than before.”

L.A. Unified officials declined to comment for this article, instead issuing a brief statement from newly appointed superintendent Michelle King: “I believe in expanding opportunities that will empower all L.A. Unified students to succeed. In order to do this, we need to eliminate the ‘us-versus-them’ mentality that is dominating our educational landscape and come together for the benefit of all students. We need to share what is working best in our traditional schools, magnets, pilots, and charters so that L.A. Unified can be the best that it can be.”

Electoral Battles

Even before the Broad plan was leaked, the charter battle had been further politicized during the spring 2015 school board elections, in which charter founder Ref Rodriguez challenged the union-friendly incumbent Bennett Kayser for a seat. In what was possibly the most expensive school-board race in history (with $3 million spent overall), the union squared off against charter supporters, including the California Charter Schools Association Advocates, the association’s political-action wing.

It was also one of the nastiest races in recent memory. District residents received flyers that pictured Rodriguez, who is gay, burning in hell for his wickedness. On the other side, CCSA Advocates attacked Kayser in a television ad featuring images of a shattering coffee mug, splashing coffee, and the tag line, “L.A. Unified is broken. Bennett Kayser is at the bottom of it.” Kayser suffers from Parkinson’s disease, and supporters considered it a veiled reference to his condition.

Rodriguez won the seat, and charter supporters won a new ally on the board. For the union, it was a huge blow. California teachers unions, whose power in the state is legendary, have rarely lost political fights. But while the election clearly shifted the balance of power on the board, the situation changed again after the Broad plan was leaked, with the school board tilting against charters.

Unionization Effort

Another piece of this battle is the year-old attempt to unionize L.A.’s largest charter group, Alliance College-Ready Public Schools. Because it seems unlikely the union will reach the threshold of signing up half the teachers at Alliance’s 27 schools, charter supporters have raised the question: Is winning really the point? Win or lose, charter advocates point out, the union fight is demanding the time and attention of Alliance’s management, thus making it harder for them to focus on academic achievement and perhaps dampening the group’s desire to expand. Again, charter leaders granted Caputo-Pearl respect points. One leader told me: “If I were trying to weaken charters, that’s exactly what I would do.”

Another bonus: now the union can champion that fight before union-friendly legislators in Sacramento, the very power brokers who make life for charters even more difficult. For example, in May a state senator who formerly served on the UTLA board successfully requested an audit into Alliance’s use of funds to fend off the union recruitment.

And Caputo-Pearl has the enthusiastic backing of his members in this fight. So incensed were the teachers by the leaked Broad plan that they voted by an astounding 82 percent to increase their annual dues by a third, to $1,000 a year, in order to combat the growth of charters. Although UTLA members are not known for high turnout in union elections, more than 50 percent of them voted on the dues increase.

Repeal Movement

All the fury has led to an effort to repeal California’s charter-school law. The group Voices Against Privatizing Public Education is trying to attract 375,000 signatures to get such a proposal before voters.

Aside from the daunting task of gathering so many signatures, however, the prospect of Californians turning against charters seems remote. California’s extraordinarily liberal charter-school law, which gave birth to the nation’s first charter-management organization (Aspire), differs from those of other states, partly because it does not require a focus on poor and minority students.

In fact, the state’s very first charter school, located in the upscale San Francisco suburb of San Carlos, is dedicated to learning through the arts. Many charters in the state provide options that appeal to middle-class parents, such as distinctive instructional designs like Montessori and Core Knowledge. In California, there’s nothing unusual about suburban charters, and the resulting broad base of support from middle-class voters will make it very difficult to overturn the law.

In L.A., however, where most charters serve poor and minority students—and appear to be doing a better job of it than many of their district-school counterparts—there is more at stake. The Washington, D.C., school district, with only about 47,000 students, was able to downsize successfully to a mix of 45 percent charters and 55 percent district schools. But no one thinks that L.A.’s sprawling district is capable of achieving such a feat: attempting to move toward such a balance would probably lead to a district breakup.

And so the fight continues to accelerate. The leaked Broad plan didn’t create the tensions, said Green Dot’s Petruzzi, but it did provide the union with the perfect PR opportunity. “The union is getting really smart around how to message this: It’s always about billionaires privatizing public education. It’s never about ‘we have to serve our students better if we don’t want to lose them.’ They have this marketing down to a science, and they are very disciplined about it.”

The union has continued to portray the charters as a drain on the district’s strength. In May, a union-commissioned report calculated that L.A. Unified loses about $500 million per year to charter schools. But the fact is, any money diverted to charters is following students whom the district no longer serves. And the union math assumes that all charter-school students, were the charter option suddenly to disappear, would return to district schools, which is unlikely. Instead of cutting staff, however, the district is trying to hold on to more students by expanding its popular magnet-school programs, adding thousands of new seats for 2016–17. The district is also pinning its hopes on an uptick in the economy and a new influx of families moving into the city who will choose traditional schools.

That’s not just wishful thinking, according to Folsom. “This city is too bold, too dynamic, and too important for [continued student losses]. The city will start growing again, and the district at that point will have to start shoving the co-located charters off our school district property because we need the space for our public school population,” he said, also noting the legal challenges involved in trying that. “And then, welcome to a whole new fight.”

Is there hope? Superintendent King acknowledges a “broken relationship” with charters and has promised to convene a summit to work things out.

And some charter leaders hope the dispute could begin to generate more light than heat. “Conflict is not always a bad thing,” said Emilio Pack, founder of the STEM Prep charter schools. “People want to make this a black-and-white thing. I like the grays. I’m a pragmatist.”

The Broad plan, recast as Great Public Schools Now, “re-launched” in June with a changed emphasis on adding high-quality school seats wherever they are found, charter or district, a clear shift that resulted from the aggressive pushback against the original plan.

But while the district can definitely work to reduce tensions with charters, the prospect of detente between charters and the union seems dim, now that the union is equipped with a new fight-charters budget and a billionaires-as-culprits strategy that pushes deficits to the back burner.

For now, the future of the Los Angeles schools remains both troubled and cloudy. It’s possible that the conflict will bring new accommodations between the two sides. But it’s equally possible that the leaked plan to dramatically increase the number of high-performing charters will, ironically, result in fewer charters.

Richard Whitmire is a veteran newspaper reporter, a former editorial writer at USA Today, and the author of several books about education.